Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

Robert Shearman may be best known for bringing back the Daleks, but as a dyed-in-the-wool Doctor Who doubter, he’s more familiar to me because of his award-winning short stories, a great swathe of which were collected last year in the deeply creepy Remember Why You Fear Me. More recently, ChiZine released They Do The Same Things Different There, an equally excellent assemblage of the author’s more fantastical fiction.

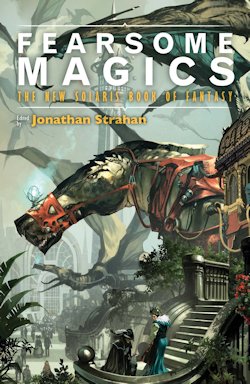

‘Ice in the Bedroom,’ the closing story of the second volume of Fearsome Magics: The New Solaris Book of Fantasy, skillfully straddles the line between the two types of stories Shearman writes. It’s as strange as it is unsettling and as suggestive as it is effective—in other words, good reading for the spooky season!

Its protagonist, Simon Painter, is suicidal when ‘Ice in the Bedroom’ begins:

He’d been puzzling at which way would be the most painless. […] Falling from a great height wasn’t too bad—and he’d heart that the body fell so fast that there wasn’t time for the brain to process it, in effect you’d be dead before you know, in effect you’d die in ignorance. But the thought of the impact. With all your internal organs smashing into one another. With your heart bursting pop against your ribcage. That was, on reflection, less appealing. And when it came to it, at the very precipice, just seconds away from oblivion, could he really swing himself over the edge? Could he ever be that brave? He thought not.

Simon isn’t exactly the most inspiring central character—indeed, like a lot of Thomas Ligotti’s leads, he’s lost in thought and lacking the will to live—but when his already terrible luck takes a turn for the worse, it’s impossible not to feel for such a susceptible specimen.

In any case, there are ways to exit the great stage, even for weaklings such as Simon—and so, at the start of the story, he talks to the doctor, having all but opted to end it by way of a blister-pack of pills. Rather like his wife did.

He, at least, would leave a note. Cathy, for her part, hadn’t. “Simon didn’t know why Cathy had done it. He supposed she’d been unhappy. Shouldn’t he have known she was unhappy? Shouldn’t she have told him she was? He felt like an idiot.”

“He probably shouldn’t have told the doctor any of that,” though. Suspicious of Simon’s insomnia, she refuses to give him a prescription. The kicker is, he really has been having trouble sleeping. When night falls, now, all he can bear to do is “stare out into the blackness of his bedroom.” And sometimes, the blackness stares back.

Simon does, finally, fall asleep. He must have done, he tells himself, because when he comes to, he’s not in his home anymore:

He looked over the side of the bed, and saw that it was sitting upon a lake of ice. More than a lake, the ice was everywhere—and it was clear, so smooth, no one had set foot upon the ice, its surface was in such contrast to the jagged coarseness of the moon, it was perfect. And yet that smoothness, it scared Simon all the more. Not a single mark upon this ice world, untouched, unspoilt, what would it feel when it woke up? Because Simon suddenly knew that it would wake up, he was so dazed and so tired and he knew nothing, but he knew this, it was a single primal truth he had been given: the ice would wake, and find him there, him and his bed sitting ridiculously on its too smooth skin, and it would open up and swallow them whole. With nothing but the pockmarked moon as a witness.

Be it real or merely a dream, the ice world scares the crap out of Simon—and indeed readers—not least because of the she-wolf which starts to stalk his sanctuary, coming closer and closer to him each time the worlds they reside in collide.

There comes a point in ‘Ice in the Bedroom’ when Simon is so far gone, in fact, that he can’t tell the two realities apart. When the she-wolf commits suicide by swallowing a knife, and his dead wife rises up out of the ice, the borders between the mundane and the magical are shattered.

The only complaint I’d make about Shearman’s story is that its structure undercuts this potentially incredible commingling. The pauses that punctuate the tale’s ten short sections are too telling: in some chapters we’re in one world, in others another, so though sleep-deprived Simon might be lost and alone, we’re never less than certain—of the ground beneath our feet, at least.

Being more immersed in the mystery of Simon’s movements would have made the difference, I think—only the difference, I dare say, between a great tale and one for the ages, because in every other respect, Shearman’s mode of storytelling is smart; soft and subtle and unsentimental.

These are entirely appropriate attitudes, too, as ‘Ice in the Bedroom’ is essentially an exploration of grief, taking in denial, anger, and eventually acceptance… albeit by way of otherworldly wolves and a living body of frozen water.

Here on the borderline between the normal and the not, Robert Shearman really is one the best in the business, whatever his business is.

I bet his Daleks are pretty good, too…

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.